I came across this article a while ago that looks at a number of query optimizations databases can make to optimize queries before executing them.

The author, lukaseder, looked at 10 sql optimizations and analyzed 5 different databases to see which ones supported the optimizations.

I’m working on a transparent proxy caching for PostgreSQL, and have been thinking about sql transformations quite a bit. I was curious to know if PostgreSQL made any changes since the article came out in 2017. lukaseder tested version 9.6 of PG, I tested version 18.0.

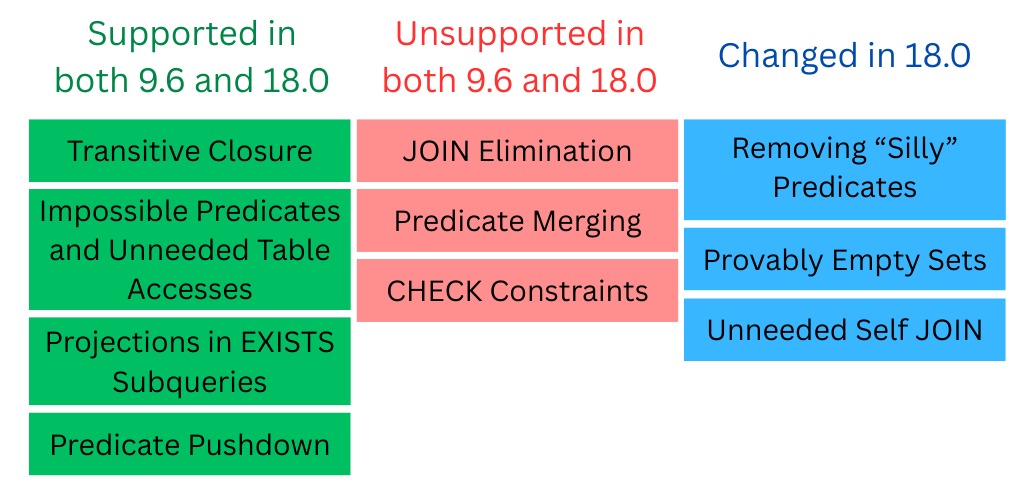

Of the 10 optimizations, PG 9.6 fully supported 4 of them, 3 remain unsupported in 18.0, and 3 optimizations differ in version 18.0 from version 9.6.

In this article we’re going to take a look at the three optimizations where some support was added since 9.6.

Before proceeding, consider taking a look at the original article to learn more about all the transformations.

Removing “Silly” Predicates

This came from wondering about what happens with a query like:

SELECT * FROM film WHERE release_year = release_year;

I’m not really sure how you end up writing a query like that in practice. Maybe if you are programmatically building queries, ending up with silly predicates becomes more likely. In any case, what do we expect to happen?

For columns that are NOT NULL, the where clause will always be true. If the column is nullable, then the clause is only true for the rows that are not null, since in SQL’s three valued logic NULL is not equal to NULL.

The NOT NULL case is equivalent to:

SELECT * FROM film;

The nullable case is equivalent to:

SELECT * FROM film WHERE release_year IS NOT NULL;

Here are the plans that PostgreSQL creates:

NOT NULL column:

explain SELECT * FROM film WHERE film_id = film_id;

QUERY PLAN

----------------------------------------------------------

Seq Scan on film (cost=0.00..65.00 rows=1000 width=390)

nullable column:

explain SELECT * FROM film WHERE release_year = release_year;

QUERY PLAN

----------------------------------------------------------

Seq Scan on film (cost=0.00..65.00 rows=1000 width=390)

Filter: ((release_year)::integer IS NOT NULL)

We can see the execution plans make the expected transformations.

I also wondered if the optimization was always made or if more complicated clauses would prevent the change. After a couple of experiments, it quickly became clear the transformation is not always made.

Using a query with an AND clause with a NOT NULL column, the optimization is applied:

explain SELECT * FROM film WHERE film_id = film_id AND rating = 'PG';

QUERY PLAN

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bitmap Heap Scan on film (cost=5.65..63.08 rows=194 width=390)

Recheck Cond: (rating = 'PG'::mpaa_rating)

-> Bitmap Index Scan on idx_film_rating (cost=0.00..5.61 rows=194 width=0)

Index Cond: (rating = 'PG'::mpaa_rating)

However, using an OR clause does not apply the transformation:

explain SELECT * FROM film WHERE film_id = film_id OR rating = 'PG';

QUERY PLAN

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Seq Scan on film (cost=0.00..70.00 rows=198 width=390)

Filter: ((film_id = film_id) OR (rating = 'PG'::mpaa_rating))

Which is unfortunate, since PostgreSQL will optimize away a trivial OR clause:

explain SELECT * FROM film WHERE true OR rating = 'PG';

QUERY PLAN

----------------------------------------------------------

Seq Scan on film (cost=0.00..65.00 rows=1000 width=390)

Provably Empty Sets

This optimization is to remove a derived table in a join when that table has to be empty. Two cases are used, one is using an IS NULL predicate on a column that is marked NOT NULL and the other case is doing an intersection where the intersection result has to be empty.

This can be a particularly valuable transformation, as can be seen in the query plans below. In the first case the query is turned into a constant. Without the transformation, a significant amount of work may need to be done.

The original article tested both inner joins and semi-joins. We’ll just look at the cases using an inner join since the results for the semi-joins are the same.

When creating a table that has to be empty by using an IS NULL clause on a NOT NULL column, PostgreSQL will optimize it away:

explain SELECT *

FROM actor a

JOIN (

SELECT *

FROM film_actor

WHERE film_id IS NULL

) fa ON a.actor_id = fa.actor_id;

QUERY PLAN

-------------------------------------------

Result (cost=0.00..0.00 rows=0 width=25)

One-Time Filter: false

When creating an empty table using an INTERSECTION clause, the query is not optimized:

explain SELECT *

FROM actor a

JOIN (

SELECT actor_id, film_id

FROM film_actor

INTERSECT

SELECT NULL, NULL

) fa ON a.actor_id = fa.actor_id;

QUERY PLAN

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Hash Join (cost=111.99..116.75 rows=1 width=33)

Hash Cond: (a.actor_id = (NULL::integer))

-> Seq Scan on actor a (cost=0.00..4.00 rows=200 width=25)

-> Hash (cost=111.98..111.98 rows=1 width=8)

-> HashSetOp Intersect (cost=111.98..111.98 rows=1 width=8)

-> Result (cost=0.00..0.01 rows=1 width=8)

-> Seq Scan on film_actor (cost=0.00..84.64 rows=5464 width=8)

Unneeded Self JOIN

This is another situation that probably arises when programmatically building queries, in this case joining a table to itself using its primary key. The join effectively creates a new alias for the same table and set of rows.

Without the optimization, the query planner and execution will perform a join operation which can end up being fairly expensive. With the optimization, the join operation is completely eliminated.

This query:

SELECT a1.first_name, a2.last_name

FROM actor a1

JOIN actor a2 ON a1.actor_id = a2.actor_id;

is equivalent to this:

SELECT first_name, last_name

FROM actor;

And we can see that the PostgreSQL planner turns the query into a simple scan without any join operations:

QUERY PLAN

-----------------------------------------------------------

Seq Scan on actor a2 (cost=0.00..4.00 rows=200 width=13)

Conclusion

When I started testing the optimizations, I was expecting (or hoping) that there would have been more improvements made to PostgreSQL. While I was writing this article, PostgreSQL 18 was released and added the Unneeded Self JOIN optimization, so it is nice to see the continual evolution of PostgreSQL.

When the original article was written it sparked discussion on the PostgreSQL development mailing list. The discussion thread is an informative look on how the PostgreSQL community approaches these types of optimizations.

The discussion revolved around weighing the value of making the optimizations to the query planner versus the cost of doing so. The cost of the planning is particularly important since PostgreSQL doesn’t cache plans by default, instead the client has to opt in to caching by using prepared statements. Without caching, the additional cost of query planning will be paid on every query, and that affects the balance of which optimizations are worth implementing.